Softie is director and producer Sam Soko’s first feature documentary filmed over the course of five years. After meeting the character Boniface Mwangi, nicknamed ‘Softie” by his close friends and family in 2013, Soko, who had directed several short music videos and films by that time, decided to try his hand at directing a documentary. What started out as a short video, that he had planned to take a year filming, evolved into a story about politics, family and what it means to be Kenyan. Four years into Soko filming chaos filled street protests against corruption, police brutality, extra judicial killings, Softie decided to run for a political seat in his old neighbourhood Starehe. Soko knew he had a possible ending for a film, and pushed to do one more year of filming as his political campaign would give a much needed insight into the political and voting process in Kenya. But the material he filmed went far beyond that and gave insight into a young family, in a young democracy that was struggling to balance their love for their country with the needs of their family, a universal story that Soko felt that audiences across the world could be able to connect to a visceral level.

Bonifice Mwangi ‘Softie’

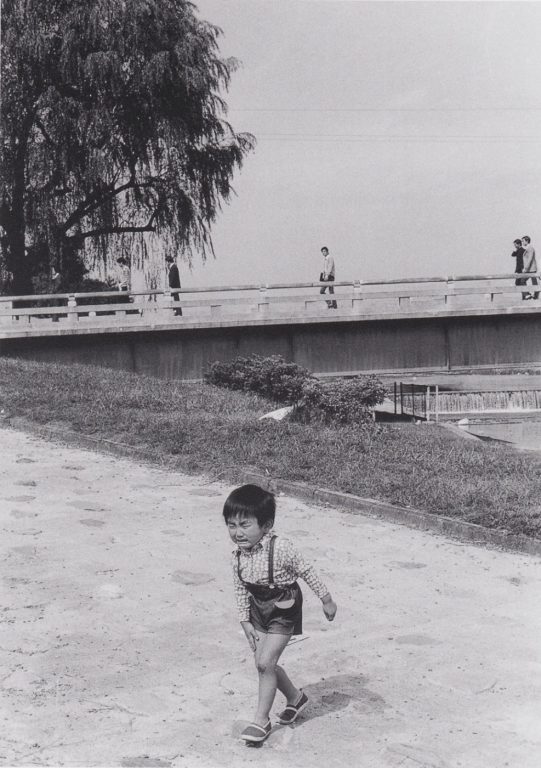

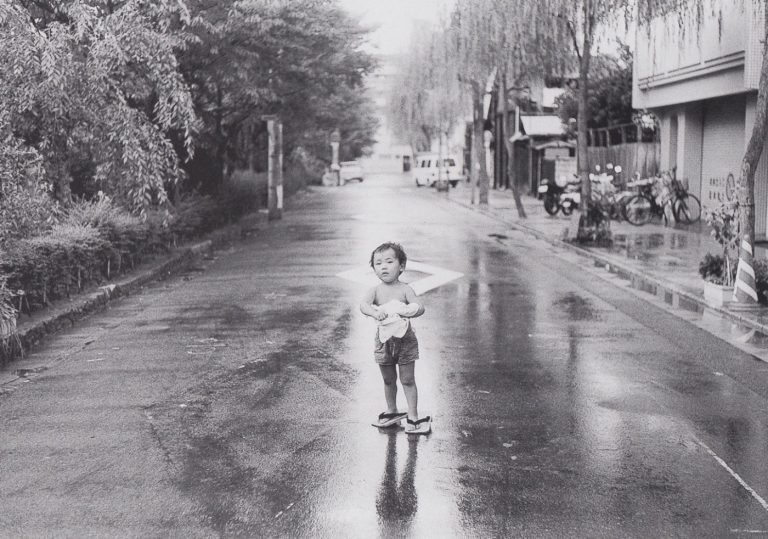

Boniface Mwangi born on July 10, 1983 is a Kenyan photojournalist, politician and activist involved in social-political activism. He is known for his images of the post-election violence that hit Kenya in 2007–2008 and his work as one of Kenya’s most prominent activists. Boniface grew up in an impoverished single parent home in Starehe county, with his six siblings. Mwangi dropped in and out of school during this period and helped his mother sell books on Nairobi’s streets. When his mother died in 2000,

Mwangi, then 17, decided he had to change if he was to survive. He joined a Bible School with the intention of becoming a pastor, and secured a diploma in Bible Studies. Whilst at school he became interested in photography.

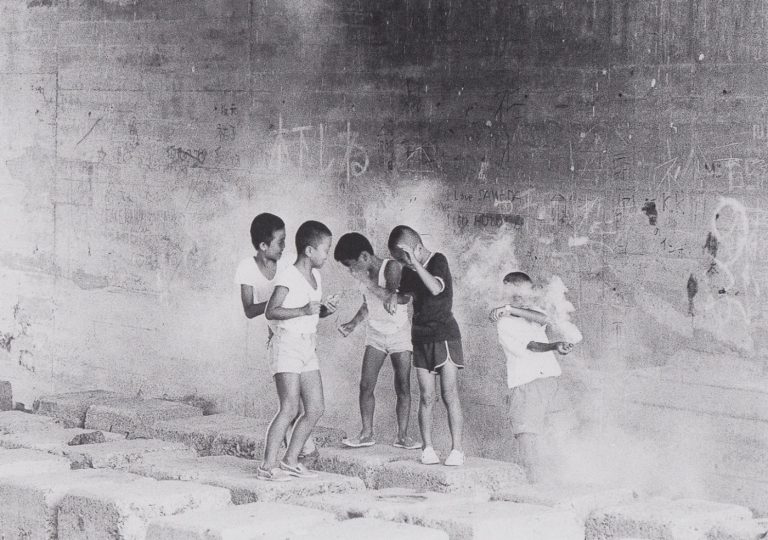

Despite not having a high school education, Mwangi managed to gain a place at a private journalism school. To fund his studies he had to continue selling books on the street, but soon began to gain experience as a photojournalist. He published photographs in a national newspaper and in 2005 won his first photography prizes. He was awarded the 2008 and 2010 CNN Africa Photojournalist of the Year Award for the photos that he took, documenting the widespread post election violence of 2007-2008. He suffered from PTSD because of all the violence that he witnessed and quit his job as a photographer to work on social justice in Kenya, mainly using street graffiti, art and street protests to call attention to human rights violations and political corruption in the country. He has been recognized as a global TED fellow for his activism work. One of his longest lasting initiatives to date is Pawa 254, a hub and space for artists and activists to work together towards social change in Kenya.

Njeri Mwangi – Boniface’s Wife

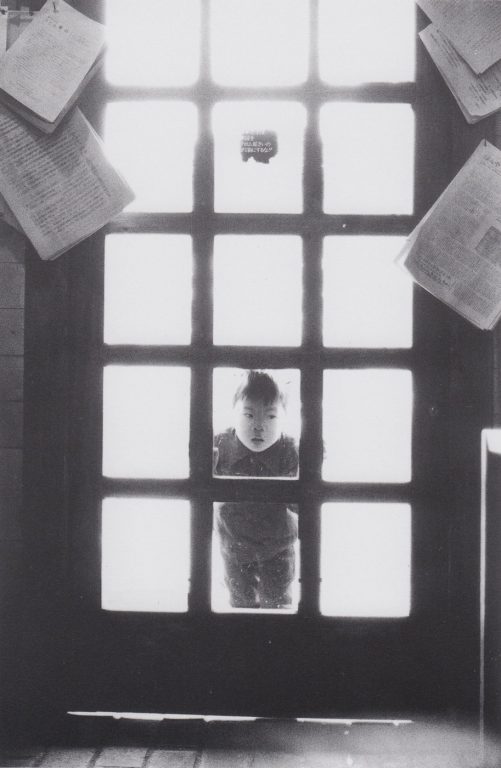

Njeri Mwangi finished college in 2005 and knew she had to work in social impact but didn’t know where. Her upbringing guides her belief in God and family first. A chance encounter at an ice cream shop with Boniface in 2006 changed her life forever. Over the years as her husband gained more prominence in public, she has remained in the shadows, raising their 3 children Nate, Naila and Jabu and Co-Founding PAWA 254 one of Nairobi’s first creative social enterprises. In 2016 her husband announced that he was running for political office. This decision made her do something she had worked hard to never do –

step out of the shadows and share her private life with the world.

Filmaker’s Statement

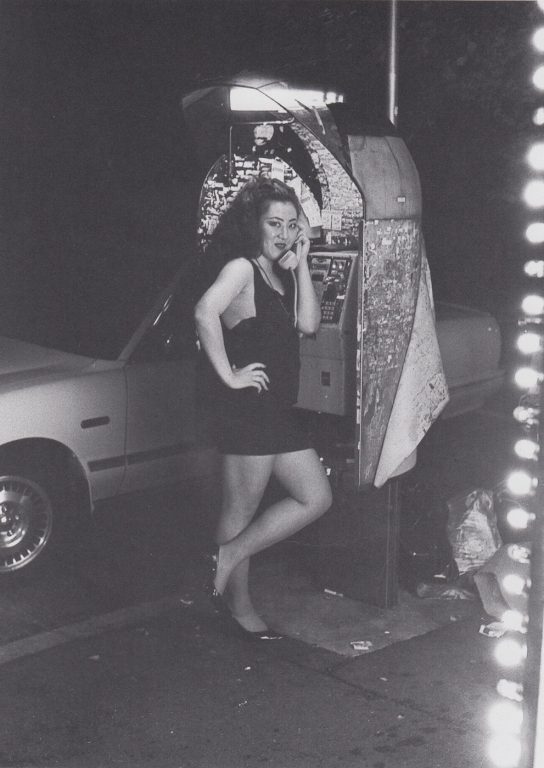

My name is Sam Soko and I love my country Kenya, however I am afraid of its corrupt and tribal establishment. A few years ago, I had the idea to develop an activism manual for Africa. It was meant to be a collection of short videos documenting the work of activists around the continent. I was inspired by the Arab spring, and wondered if a similar wave of protests against despotic African leaders was in the offing. That is how I met Boniface Mwangi, Kenya’s most infamous activist. Four years later what was to be a manual has turned into an intimate visual portrait and story documenting the thrills, fears and sacrifices of being an activist. One important question I had four years ago and still do, is what are the implications of living such a life – to the wider community and to one’s own family? In this case what comes first, family or country?

The story is set against a backdrop of historical injustices, which have been used by post independent Kenyan governments to fester hate between people who generally share similar cultures. It is ironic that our current leaders use the same tactics that our former colonizers did – divide and rule through creation of “fear of the other”. This is done to sustain an even greater obstacle of progress. One which Kenya’s Chief Justice explained by saying, “Most countries have a mafia; in Kenya the mafia have a country.”

This is in reference to how corruption and bad governance had entrenched itself in my country’s day to day life. Kenyan leaders have found a way to divide people using tribal affiliation and voter bribery. Our country has grappled with ‘Fake News’ for over 50 years. Kenyan politicians have spent decades perfecting the dark art of spreading deep falsehoods amongst people, to make sure they despise one another. The outcome is that every 5-year election cycle is characterized by violence. The worst instance of post- election violence was in 2007 when over 1400 people were killed and hundreds of thousands of Kenyans were displaced within the country. Incidentally, it is this violence that brought the main subject of this

story, Boniface Mwangi, into the national and international spotlight. As a young photographer he documented this violence, winning several global and local awards for his bravery, covering the stories of survivors. Boniface life was forever changed from then on, turning to activism as a means to push for positive transformation of Kenyan leadership. This is how I met him.

I came to realize that the life of an activist conceals many things. As they are up against a society, whose mindsets are difficult to change, they also have to deal with their own families. Boniface’s wife, Njeri, has emerged as a critical element of this narrative. As a witness to what lies beyond the activist and politician that is Boniface, she has provided a rare and remarkable view into the sacrifices that families of activists have to make in their quest for social change.

Boniface and Njeri are Kikuyu. The Kikuyu are the largest, out of the country’s 42 tribes. This is the one thing they have in common with the ruling class, led by our current president, Uhuru Kenyatta, who is the son of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. Boniface’s beliefs mean he is viewed as a traitor by his tribesmen and some of his family. From dynamic protests, death threats, family fights and life changing decisions, this film tells the story of their unparalleled journey. In a world where sowing seeds of division continues to be encouraged, I believe telling this story will inspire audiences across the world to fight for justice and a more equal and inclusive society, in their own way.

I have been filming over four years, capturing Boniface and Njeri’s story in an intimate, observational style. At points the characters are aware of the camera and interact with it. This approach creates a very personal and close understanding of both of them. I have also interviewed them separately which allows for their different perspectives to be reflected in the film directly. Most of the principal filming is done and we are looking for the right creative partners and financing to make sure the story fulfils its amazing potential.

Making The Film

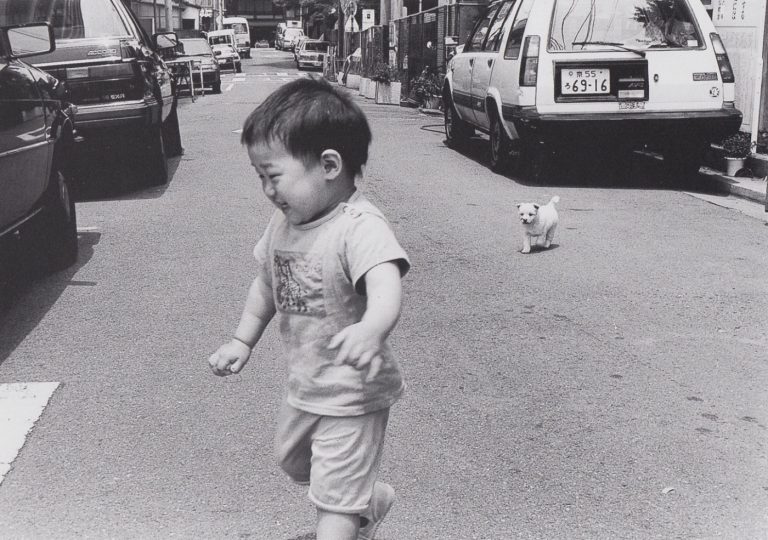

After meeting the character “Softie” in 2013 at a protest rally, Sam Soko was initially inspired to develop an activist’s manual. The initial goal was to produce a simple quick, short 20 minute film in less than six months and distribute the short video manuals on youtube, and go back to directing music videos and fiction films through his company Lbx Africa, which he co-founded with his long time friend Bramwel Iro . But, like all great stories, it wasn’t that simple at all. Soko grew to know Softie well, and saw that underneath Softie’s tough man exterior, was a complex, vulnerable and deeply passionate person who got into activism for very personal reasons. Softie got his nickname as a child for being seemingly harmless and weak. As a child, Softie was bullied for being dirt poor and the child of a single mother. This difficult upbringing spurred him on as an adult, as he was literally consumed with ensuring that no one else experienced his childhood poverty. And Softie went even further, embracing the cruel childhood nickname as an adult, which is now used as his nickname by close friends and family. He was not going to let the bullies win. That’s the kind of guy Softie is.

After four years of filming, becoming friends off camera and getting to know his wife and family well, Soko knew he had more than a straightforward activism manual in his hands. And that he needed a bigger team to help turn this into a film. The team soon found Soko one by one. Doc Society joined the team in 2017 with Sandra Whipham and Jess Search serving as Executive producer, and this was through a fortuitous meeting at a filmmaker gathering in Nairobi. Toni Kamau, joined the team as producer in early 2018 and Mila Aung Thwin, who had mentored Soko as a Hotdocs grantee in 2018 joined as Editor and Executive Producer along with Bob Moore. The team achieved early success by winning audience award for best pitch at Hotdocs Forum in 2018, and a co-production with POV for US public broadcast. And since then it’s been two years of late night skypes, midnight edits and festival get togethers as the team, spread out across the UK, New York, Canada and Nairobi joined forces to turn 800 hours of footage into a 96 minute feature documentary. The story of how Softie got to be made into a film is a testament to the power of belief, the importance of human connection and above all else the power of collaboration. Softie is produced by Lbx Africa in collaboration with We are not the machine Ltd and Eyesteelfilm.