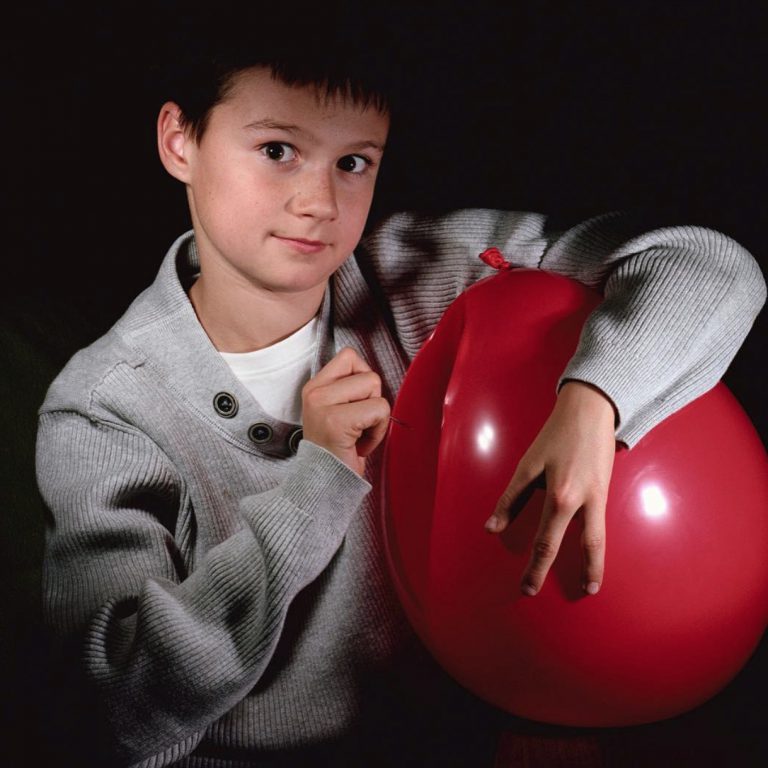

In rural Tennessee, Austyn Tester, a 16-year-old newcomer to the live-broadcast ecosystem, attempts to ride a wave of optimism to become the next big internet crush. Teen girls all over the world tune into online “boy broadcasts” like Tester’s, in a 21st- century version of Tiger Beat, where all your fave heartthrobs might actually interact with you online for a minute or two — or more for the right price. But Tester’s earnestness sets him apart, peering wide-eyed into his laptop camera and professing that his female fans matter for hours on end. What’s he selling? Male validation. In return, he asks for fame and a better life for his family.

From meet-ups at the mall to a full-fledged boycrush “roadshow,” girls fork over the cash for the chance to hug and kiss their boy. Director Liza Mandelup documents the rise of the teenage Svengalis who control this economy and offers a judgment-free window into their dealings, dramas, and ultimate success or demise. She counters these depictions of the fame-hungry with interviews from girls whose candid admissions of desire ring painfully true. Tester genuinely wants to make the girls feel good, but will his open heart give him celebrity status and a chance to escape an abusive past and a dead-end town? Or is this new ecosystem built for failure?

Mandelup’s feature debut, JAWLINE, distills the most complex concepts about modern- day childhood and a gold-rush teen economy into one fascinating and surprisingly moving human portrait that questions what values we’ve passed onto our youths, and discovers a new and fleeting American dream. Mandelup approaches this peculiar world with an intimate air of BFF confidentiality and finds that as esoteric as the internet and its niches feel to some, boy broadcasts represent modern youth’s starvation for love and acceptance and susceptibility to exploitation — a tale, unfortunately, as old as time.

A Conversation with Liza Mandelup – Shooting the Dark Side of Dreams

Liza Mandelup began her career as a photographer. She traveled around on the kinds of adventures that would bring her face to face with fascinating free spirits — train hoppers, female bikers, club kids — and possessed the confidence to approach them and make them feel comfortable in her presence. Her early photo series are a cataloguing of these wind-swept times and people; it wasn’t long until a prominent casting director spotted her eye for scouting talent.

“I first did a scout for a huge Levi’s campaign, and I realized that the job was something I do naturally in my life, I traveled around and talked to strangers I thought were interesting. I loved finding talent and met people I began making films with while casting for brands. A lot of my early work was made while simultaneously working as a casting scout.” Mandelup explains that the experience evolved her thinking about filmmaking.

“I used to think documentary filmmaking was just that you get access to a doc subject through this magical thing that happened, where you crossed paths, and everything falls into place.” But Mandelup says casting real people for ad campaigns reversed her process. “Instead, I dreamt of subjects and went out looking for them — and thought of potential stories and found people who could possibly embody them. That was my process for making JAWLINE. I’d already done the research. I knew the world and I had the character in my head. We filmed for a while before we even found my ‘lead.’ I wanted to film with him on the first day he decided he wanted to broadcast his life in hopes of becoming famous — and see where that desire took him. Who knows what will happen? That was the mystery: ‘Will it crush him?’ or ‘will he actually succeed and we’ll watch him become famous?’ I pitched that around, and one manager told me they’d found Austyn Tester randomly online. I flew to Tennessee to meet him and we knew right away he was our feature.”

Though JAWLINE is documentary and so necessarily requires off-the-cuff interviews and fly-on-the-wall cinematography, Mandelup has never abandoned her aesthetic sense as a photographer.

“I’m really obsessed with framing and style,” she says. “It’s not good enough just to get the scene. I try to do as many things as possible to make it look cinematic and collaborate with people who work in this space as well. I picture my documentaries playing out like a narrative, but we have all the challenges of chaos working against us. When things actually look good, it feels magical.”

Of course, Mandelup can’t simply interrupt her subjects or DP in the middle of filming to direct them, but she prepares for the moments when direction must be given. “The DP, Noah Collier, and I had so many conversations about what to do with movement or framing when certain scenarios arise. How do you make something look really beautiful when you don’t have any control over what’s happening? But, my crew becomes friends with everybody they film with. Everyone knows that, above all, we’re there to integrate into these people’s lives before and after the cameras are rolling. It allows us to create a blur between personal connection and what we get on camera. Nobody is on the clock. The goal is to make the process seamless.”

Ask Mandelup her style, and she’ll use the word “dreamy.”

“Everything I do links back to dreams,” she says. “I follow people’s fantasies. Their desires and the emotions behind that — the story elements are one thing and we are always working on that while filming and editing, but that emotional layer is something else that I work on making sure never gets diluted. I care about how people are dealing with their emotions, timeless elements that will last long after the technology in the film has gone. I want JAWLINE to feel like a teen girl’s fantasy, an all-access pass to intimacy. To the secret lives of boys. But, there’s also a dark side.”

All this beauty Mandelup creates is a red herring. JAWLINE appears as a pastel fantasy, pretty and pleasant to look at, while telling a more nightmare-ish tale of late-stage capitalism. “We’re gonna paint this fairy-tale world where people are doing really fucked-up shit. That’s part of the concept behind making JAWLINE so bright and dreamy,” Mandelup says. “In this world that I’m documenting, everyone’s exploited.”

Mandelup breathlessly lists the ways in which the “boy broadcast” economy impacted the teens’ lives, how kids all over were dropping out of school to sit in front of a computer screen, leaving them ironically more disconnected, less able to relate to the kids in their own schools and towns, and reality. “People want to be spoon fed the hard facts, but I like to show the viewer what’s happening and the emotions involved and let them form their own opinions.”

Mandelup describes showing an early cut of the film to some people. She laughs when she recounts a comment from one that asked: “Does she know how dark this is?”

“JAWLINE is a reflection of what I saw happening with some teens right now, anxiety and isolation is exacerbated and they’re going to new lengths to cope with it. It’s not just bedrooms painted black. The new teen rebellion is hidden between screens, it’s not as obvious, you have to really go looking into these apps to understand what’s happening here,” Mandelup says.

“But if you’re feeling uncomfortable with it, if you’re wondering what the hell is happening, you’re not reading into it. That darkness is there. The first thing I said when I started this film was: ‘This is fucking dark.’”

Love in the Time of Live Chat

Mandelup thought her film would be a love story: “I wanted to make a story about teens in love, with the backdrop of technology and how that factors into how they live their lives.”

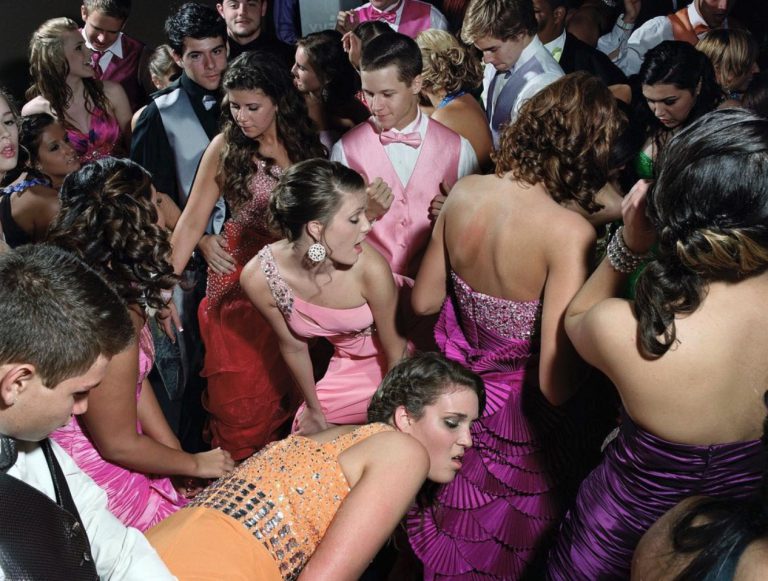

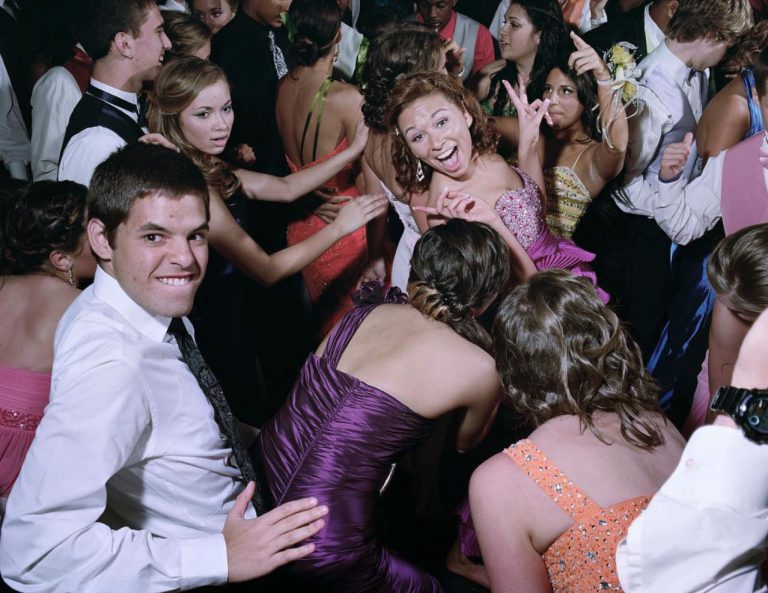

In her research for niche online communities, she stumbled upon conventions, wherein teen girls could pay to meet the guys they were following online through a live- broadcast app. Mandelup was struck by the “spontaneous, bizarre emotional connections” she witnessed in malls and trampoline parks as the girls rushed to embrace and get a picture with their online crush. The result of that scouting was a short film entitled “Fangirl,” which featured three teenage girls who feel an unconditional love towards their online crush. Mandelup was still hung up on what she’d seen — the frenzy around these boys was akin to what happened with the Beatles. But these boys weren’t peddling art. Their wares were emotional validation.

“I felt like I had to unpack the emotion behind this,” Mandelup said. “The fangirls’ obsession with getting to know these guys through a live-streaming app got me curious: Why these guys? What is so interesting about them? What do they do to cast a spell on hundreds of thousands of teenage girls while being completely regular guys? My immediate thought was that they were giving a kind of love. Connection is all about getting to know someone, being intimate with them, and these boys were doing something on this app that felt similar, live broadcasting day-to-day life, giving girls affection. And for girls longing for this, that kind of interaction, well, it feels a lot like falling in love.”

Throughout the film, Mandelup sprinkles in candid interviews with these girls, who are startlingly comfortable revealing their inner lives to the camera, perhaps a side effect of

a life lived online. Each interview, though disparate, carries similar traits, usually a proclamation that the boys and men in their lives had been cruel or abusive to them, and chatting regularly with some nice boys — though they are strangers who happen to also make money off the girls — renewed their self-esteem and faith in the future.

What’s remarkable is the girls’ self-awareness, the understanding that they are paying for a fantasy. Mandelup thought the boys to be gender-reversed “cam girls” in a sense. “The girls in the film need something that is not necessarily sexual, though. They need love,” Mandelup says. “But for all genders, sexualities, it’s different. The market of it, how desire is bought and sold online. There’s no such thing as ‘fanboys’ in this specific world, for instance, because it’s built on a ‘falling in love’ that doesn’t seem to work in reverse.”

Mandelup mined her own childhood emotions to find an avenue into this world. The process was in a sense similar to that of Bo Burnham’s for the making of Eighth Grade, wherein the story is wholly informed by going to the teens themselves and asking them what they fear or adore, rather than adults simply projecting their best guesses onto the screen, or trying to pigeonhole kids into rigid character confines. JAWLINE and Eighth Grade, though totally different projects, together mark a new-ish form of authentic filmmaking perhaps not seen since the days of Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

“For me, I think the whole process was me tapping into that teen mentality and trying to find common ground with it, through the process of filming and meeting these people.” Quickly what initially mystified Mandelup became second nature to her.

“When we were filming with them, I realized that under the surface, the teenage dynamic is still the same. It just now exists with technology as an extension of the self. It’s creating a hyper version of social dynamics that may have existed in the past — these are age-old emotions on steroids, being fed to you through a constant stream of live- broadcasting.” Mandelup describes the booming economy of boy-chatting to be the “wild west.” But not everyone makes it rich in a gold rush.

“The people profiting are businessmen who’ve hopped from one venture to the next, and they saw this economy happening, like ‘Oh, you have all these girls who follow you, and every time you tweet you’re at the mall, they show up and buy you things?’ A lot of these boys come from nothing and are being quoted numbers that are unrealistic, but both the girls and boys are being exploited. The managers will be the first to tell you the market is capitalizing on teenage girls’ insecurities, and as long as there’s money and fame in it, these boys, represented by these managers, will be there to offer the ‘confidence drug.’”

Even though the focus of JAWLINE isn’t the girls, their voices frame the film. “The girls were more, like, power in numbers. It never felt as though one girl’s story told it all. In the beginning I thought I would have one girl character opposite the boys, but when you notice there’s dozens and dozens of girls feeling anxious, lonely, getting bullied, and wanting to harm themselves, it became obvious they could only be an ensemble.” Mandelup describes them as the “chorus.” With JAWLINE, it’s impossible to see the boys without seeing them through the girls’ eyes.

“In this story, the males are objects of desire,” Mandelup says. “This is Austyn Tester’s story, but through the female gaze.” Despite the industry preying upon their insecurities, however, the girls still hold a power that even they seem unaware of, Mandelup explains. They wield the power to mature out of their momentary desire for synthetic love, but until then, Mandelup says, “Ultimately, they decide who is worth sticking around for.”

Finding Austyn

Mandelup started this film with a two-person crew: Herself and her DP, Noah Collier. Traveling from convention to meet-up to convention, she interviewed hundreds and hundreds of girls in fifteen states but always had her eye on gaining access to the right boy to tell this story.

“These traveling shows happen all over, and it’s much harder to gain access to them than you’d think,” Mandelup explains. “I’m really transparent with how I pitch everything — this is an indie artistic documentary. I give them my site. I tell them where I see the film going. But this world of the boys, it’s about fame and celebrity. They weren’t trying to get into the art world, and I was coming from that angle.”

Through this process, Mandelup also realized one key element was missing from so many of the boys: She needed to find someone who seemed genuine and who had high stakes in making it in the live broadcast world.

“Yeah, there were times where it felt like I didn’t like the guys. I loved the girls, but finding boy broadcasters that I connected with was a bit harder. I wanted to sympathize with my subject — I couldn’t do that for someone who had bad intentions. I need to want the best for them in order to film with them so much.”

When she finally met Austyn, the lightbulb clicked on.

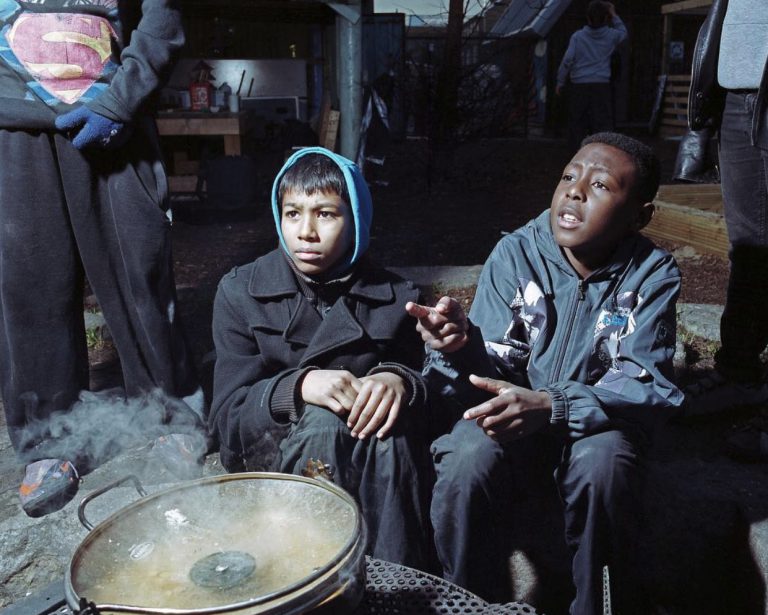

“We went to Tennessee and met his family and saw the dynamic of his house, and there was a story in every corner.” In the film, we see bunches of kittens roaming around a squat ranch home, framed by clutter and worn furniture. Amid this is a tightly knit

family rooting for a teen boy who’s got a chance at fame he won’t take for granted — he says with wide-eyed optimism that someday he’ll “change the world.”

“When I met Austyn, he was so naïve, in a beautiful way, the kind of naivate that only happens once — before you’re met with reality. He was just utterly convinced that if you dream something big enough, it can happen, no matter what’s working against you. And the odds were against him. His whole family was relying on him, and it was the opposite of what I’d seen with the other boys. He was trying to help his family and help other people. The second I met him, I thought that this film might go, he might be famous, and I was attracted to it.”

Mandelup calls Austyn “genuine” and describes the moments when they would stop filming him as he chatted with the girls, and how he would continue talking to them for hours. But Mandelup asks: “When you want to be real to people, does that serve you in becoming internet famous in a market built on a self-fulfilling prophecy like stardom? The girls are escapists looking for an outlet to try to cure this teenage isolation and disconnectedness — and Austyn happened to give them a love drug. But Austyn has those similar feelings. He can’t connect to anyone in his town, and nobody there acknowledges his dreams. People bullied him and made fun of him. That he wants something more than fame sets him apart from the other boys. But this is also a one- sided economy.”

Austyn’s full story certainly could not be told without explaining his economic background, but Mandelup chose only to show small details of his everyday life. “Nobody pitched Austyn to me like, ‘Oh he’s very poor.’ I met him without knowing his circumstances. I was just told that his character would win me over. But when you come from nothing like Austyn does, it makes it even more compelling that he would get it in his head that he could become famous. There’s no one in his life telling him this is an option — he created this mentality himself.”

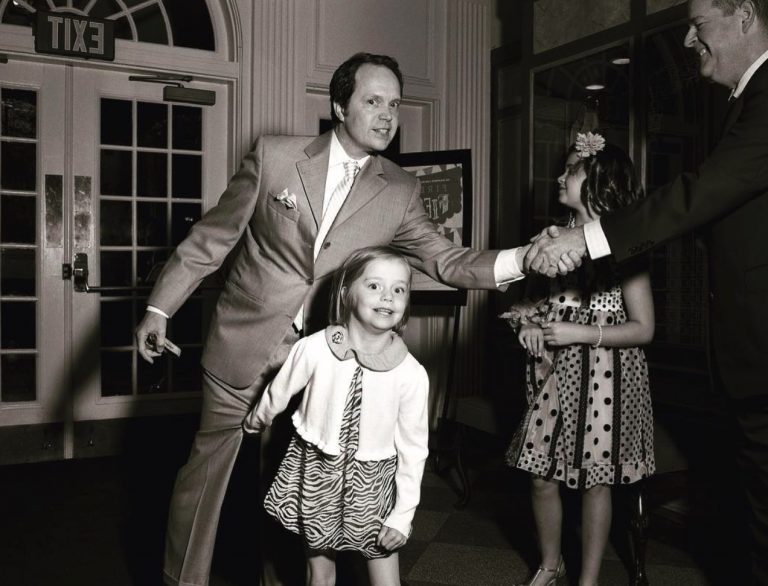

In JAWLINE, Mandelup has tried to wrap her head around the new ideal of an American dream. It was imperative for her to cast a kind of Goliath to Austyn’s David, which is how she came across Michael Weist. “When I met Michael, he was 18, and he actually approached me and inquired about what we were filming. When we started talking, he told me he was the CEO of his own multi-million dollar company. I was like, ‘If you don’t have a movie about you, I‘d be shocked.’ I realized this is a teenage world, for teenagers, run by teenagers and the whole economy dependent on teenagers. It’s the epitome of the internet age, the idea that ‘Oh, we’re going to skip everything and be our own ecosystem. I’m going to manage you and run your profits.’ There was no need for an adult in this equation.”

When Mandelup began filming in Michael’s “boy broadcast concept house,” she was taken aback by this world the young entrepreneur had created. “The idea for Michael

was like, ‘I’m gonna have a bunch of boys live in this mansion, and we’re going to broadcast 24 hours a day, and they’ll collaborate on videos, and we’ll make the most content ever.’ The boys had free reign over this beautiful, luxurious house Michael provided, where they could chill and play video games and be messy, while broadcasting their glamorous, fun lives.”

That Austyn, living in a home with shoddy plumbing and sharing a bed with his brother, would somehow dream of fame became less and less mysterious to Mandelup the longer she spent in this world.

“The new American dream is being dangled over you with a carrot. It’s no longer this distant thing. Fame is iconic in American culture. Now, because we all have access to the internet, it feels attainable. Kids are no longer subject to their surroundings. ‘Instead of staying in this town I hate and getting bullied at school life, why can’t I become famous?’”

With JAWLINE, Mandelup was chasing down desire, but she was also searching for this new American dream. She traveled all over suburban america for this film, and everywhere she went, someone asked her to subscribe to their channel or watch their broadcasts. Was the chance of fame just a numbers game rigged for the privileged? And for how long can this whole enterprise be sustained?

“Right now, as I’m talking, this booming economy we shot, it’s probably already dried up. I think it’s already done. This whole ‘boy broadcast’ dynamic, it was just a glitch, a glitch that happened where this concept landed, and there will be another and another to follow it. It was an illusion to begin with. Michael calls it the ‘social media gold rush,’ but the gold was already gone by the time many of our characters were looking for it. That feeling of these boys knowing they are destined for something bigger may never disappear now, even if that economy is gone. What I learned is that to get big in the this world, you skip a lot of reality. The implications of this can get dark. These guys are told they’re disposable, and there’s only a small window for the girls when they think they require this external validation. Still, in every single town we went to, this was the new American dream. They want to be famous and they don’t need to rely on talent to become that. JAWLINE, for me, captures this fleeting moment in time.”